It happens. At some point in your management career, someone is going to try to maneuver you into doing something risky, ill-advised, or just plain stupid.

And the most likely tool for this manipulation is a project’s cleverly manipulated financial analysis.

I’ve seen it done with cost reductions, new product development projects, capital expenditures, expansion projects, and even acquisitions. A prudent manager is well advised to be on the lookout for examples of the “primped pig” when they review project proposals

What are they really trying to do?

I’ve observed two distinct underlying motivations for this type of game-playing:

- The manipulator has an agenda.

- The manipulator really believes in the project, but can’t get it to “pencil out.”

Usually, but not always, those engaging in the first type of project manipulation have some ulterior political motive. I’ve seen instances where short-timers (specifically, those who will soon be promoted or transferred) use project analysis manipulation as a way to pad their track record. The thinking is that they will never be taken to task for launching a project that is doomed to failure, as the disaster will likely be blamed on “bad implementation” by their successor.

In one example, a senior executive (soon to be promoted) advocated an absurdly high valuation for a company he wanted to acquire. At the time, the prevailing opinion was he would soon become my boss. Unfortunately for me, the deal’s most outrageous assumptions laid with a portion of the company that would be mine to manage if the transaction was closed. If I hadn’t challenged him, I likely would have been saddled with a business with vastly over-inflated expectations and little hope of placing the blame where it belonged when those expectations failed to materialize.

Another flavor of “agenda” is when the primary advocate wants to embarrass a competitor or enemy. This can be accomplished by saddling the target with unrealistic or unreasonable performance expectations, while making the balance of the project readily achievable. While doing this requires a lot of plotting, I’ve repeatedly seen it done on large projects. In those situations, one particular person has inadequate budget or resources to accomplish their assigned part of the total project, and rather than questioning the original plan, blame is typically placed on the person who didn’t deliver what was “promised.”

More common, however, are situations where the manipulator is “just trying to make the project work on paper.” Usually, these projects are the ones that intuitively seem to make sense, but when the spreadsheets are built and the numbers are run, look like a poor idea. I’ve seen many instances of “assumption massaging,” where a mediocre or even bad project suddenly looks good in the spreadsheet.

A particularly notable example was a new plant proposal originally suggested by the CEO. In principle, the new facility cleaned up a messy situation where assets and costs were shared between two different divisions. Unfortunately, assumptions in the financial analysis had to be adjusted to the point that there wasn’t any hope of actually delivering what was being promised. I’ve often wondered if the CEO participated in the “adjusting” process, or if his subordinates simply realized the way to play this particular game was to give him what he wanted. If the latter explanation is correct, he sure didn’t look at the final analysis very closely!

How do you spot The Pig?

There is no substitute for closely studying any and all project proposals. I know it can be tempting to skim through a twenty-five page project proposal, and even more tempting to avoid the details when they look daunting. But just because the person making the proposal appears to have treated every aspect of the project, there can still be gross errors of the type you will only uncover by being extremely thorough.

Here are some generalized steps that should help you avoid trouble:

- Read through the project and identify every assumption being made. Put them in a list and then make your own estimate of high, low, and most likely outcomes. If you find too many of the project’s assumptions are wildly favorable, there is likely some serious “shading” going on.

- Have a couple other people you trust read the proposal looking for the same thing mentioned above. Compare notes.

- Try not to let the decision swing on a single assumption, but instead continuously keep in mind entire proposal. I’ve seen managers zero in on an obviously incorrect assumption that, once fixed, doesn’t change the outcome of the analysis. In many of those instances, they still miss half a dozen other overly optimistic assumptions that will never all come true.

- If you’re going to rely on backup plans to cover for the project’s greatest risks, then subject the backup plan to the same level of scrutiny as the base project. What are the assumptions, costs, and when will you realistically pull the trigger to execute the back-up? Financially model a realistic scenario.

- Make sure “downside” scenarios really represent the downside, rather than just minor variations of a few key assumptions.

- Look at the proposer’s track record. If they’ve got a history of being over optimistic on assumptions, expect that to continue.

- In your largest and most critical projects – the ones that could sink your career – get independent, outside eyes on the proposal.

I wish I could say I was wildly successful by implementing these precautions, but that wouldn’t be true. While I occasionally employed a few, I was often suckered into approving projects with fluffy assumptions and unrealistic returns. Making mistakes was at least as much about me falling in love with the project concept as it was failing to find the project’s weak points.

Eventually, it caught up to me – a particularly critical new plant proposal and an acquisition, both with plenty of high-risk assumptions built in, hit the skids at the same time. Had I been more objective while evaluating the proposals, I probably wouldn’t have completed either one of them. Instead, I let emotion and a well-crafted spreadsheet sway me. I ended up paying for those mistakes with my job.

Conclusion:

A high degree of career and performance risk is wrapped up in project proposals, and a prudent manager brings his/her best game to the evaluation of such proposals. It is critical to identify key risks, and look at the project holistically and objectively, rather than falling in love with it and letting emotions carry the day. 30.3

Other Recent Posts:

- New Hires and How to Increase Your Odds of Making a Good One

- Acquiring Companies with “Illegal” Workers

- The Vindictive Boss

- Preconceived Notions

- Wishing-Doesn’t-Make-it-Real

- How to Handle a Hot Potato

- Horsetrading in Negotiations

If you are intrigued by the ideas presented in my blog posts, check out some of my other writing.

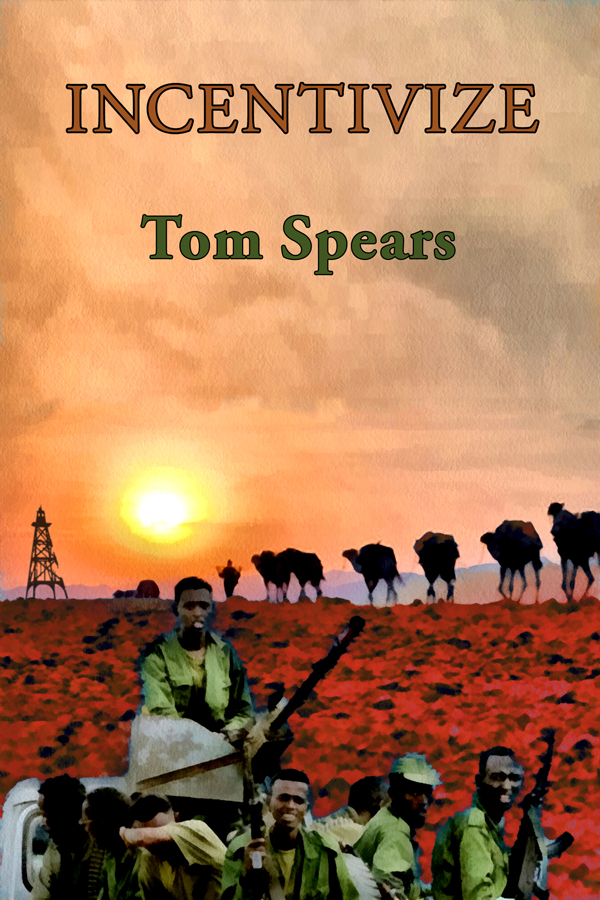

Novels: LEVERAGE, INCENTIVIZE, DELIVERABLES, HEIR APPARENT, and PURSUING OTHER OPPORTUNITIES.

Non-Fiction: NAVIGATING CORPORATE POLITICS

To the right is the cover for INCENTIVIZE. This novel is about a U.S. based mining company, and criminal activity that the protagonist (a woman by the name of Julia McCoy) uncovers at the firm's Ethiopian subsidiary. Her discover sets in motion a series of events that include, kidnapping, murder, and terrorism in the Horn of Africa.

My novels are based on extensions of my 27 years of personal experience as a senior manager in public corporations. Most were inspired by real events.