Who do you trust? What do you trust them with? These are two key questions that senior managers grapple with on a daily basis. Trust too little, and you’re severely hampering you productivity, making you into your own chokepoint. You’ll smother subordinates, leading the better ones to quit, and take criticism from above because too little is happening too late. Trust too much, and you risk letting things spin out of control as unqualified employees assume responsibilities they aren’t ready for and race along making one bad decision after another.

Somewhere in between these two extremes are various points along the continuum of trust and delegation that are workable. Depending on your personal style and the culture of the organization a lot of these can be made to work successfully.

But when it comes to major projects, initiatives, or strategies, you’d better “make sure” no matter how much you’re normally willing to trust others.

High Stakes

Many managers seem to struggle with separating the wheat from the chaff. They seem to see delegation as an all or nothing game. They lump subordinates into categories of trusted or untrusted, and apply that label to everything they are involved in.

Better managers recognize that they can delegate more when the stakes are low, and less when the stakes are high.

The best managers realize that there are a class of decisions that are so critical to the organization’s success or failure that nothing short of conducting their own, independent “due diligence” will be satisfactory.

The doomed factory

Late in my career, I came into a new job in the wake of a key decision to open a new factory. It didn’t require any brilliance to realize that the quality of this decision was going to be a key determinant in my success or failure over the next several years.

By this time, I’d been around the block a few times. Earlier in my career, I might have simply decided that this call had happened before my time, and my job was simply to make the best of it – good or bad. Now, I realized that since my performance was going to be determined in light of this decision, I’d better understand its underlying assumptions, and the analysis that supported its justification.

I quickly realized the original project looked like one where the executive sponsor said to the financial staff: “give me an analysis that supports opening this new factory.” The analysis read like a poor work of fiction. Even critical assumptions – such as productivity gains in the new facility – appeared to be pulled out of thin air.

Ultimately, I decided there was no way to succeed in the position without nuking this plan. Unfortunately, my current boss was the sponsor, making that option virtually impossible. I left a few months later.

Not always ideal

Theoretically, the best way to handle the above issue would have been to thoroughly review the justification for the factory BEFORE taking the job. But that isn’t always practical. In this case, the analysis was considered so “secret” that I had trouble getting my hands on a copy even after I was in the job.

For these absolutely critical decisions, however, there is no substitute for rolling up the sleeves and working through the analysis on your own. Only then can you find the absurd assumptions, outright mistakes, or intentional subterfuge that will cause you great grief down the road.

IT Soup

Throughout my career, I’ve seen more senior exec wreck their careers over new IT systems, than over any other single issue. Yes, IT systems are complicated, their implementations are highly technical, and the issues are not necessarily obvious when you start down the road of beginning a migration.

I’ve been through eight of these things over the years, and know that doing a thorough “due diligence” is absolutely critical to success. Since I lacked the technical expertise to understand all the details, however, I employed an investigative strategy that has served me well on almost every project. I begin with a very skeptical view of the justification, figuring the required costs and times will be much longer than expected, and the savings much less than expected, at least until someone can convince me otherwise. I also employ independent, outside experts to conduct assessments at critical junctures.

While I can’t say they’ve all gone smoothly, I’ve never had a complete system meltdown, or caused the business to falter as a result of a new system conversion.

Not just for M&A work

Companies routinely conduct thorough reviews of acquisition candidates, including using outside experts, when a deal is proposed. Why don’t we subject our major, critical internal decisions to the same level of scrutiny?

Because we are already assumed to be “experts?” Because it can be slow and expensive? Or is it because we might not want to hear the results?

New technology = high risk

One of my biggest managerial failures occurred when I placed a big and inadequately researched bet on a new technology. I compounded this by relying on the wrong people to give me comfort that the technology would work.

In this case, I had (or could relatively easily acquire) the expertise needed to validate the assumptions surrounding this particular project. Unfortunately, I was in too much of a hurry to actually do so. Instead I relied upon the assurances from a subordinate – one whose past track record should have set off warning bells in my head – and a supplier who had his own agenda, one the project would serve quite nicely.

Had I personally checked out the technology, had I sorted through all the underlying assumptions to find those that were suspect, had I brought in outside experts to validate the proposal, I probably would have avoided what turned into a major disaster.

But I didn’t. I was guilty of exactly the same thing I saw happen later with the doomed factory.

I wanted the analysis to be correct. I kept pushing people to “sharpen their pencils” until I got the answer I wanted to see.

I only later realized I created a house of cards, putting my trust in those who didn’t deserve it, and failing to pressure test the proposal.

Conclusion

Trust is a tricky thing. Too much of it or too little of it can both get you into trouble. When the stakes are extremely high, however, there is no substitute for an open, questioning mind, and as objective an evaluation of the facts as can be had. My preference is to perform that examination personally, supplemented by subject matter experts where my own knowledge falls short.

By performing your own due diligence in this way, you can avoid many of the disasters that can crater your career. 27.1

Other Recent Posts:

- Do what you believe is best, or what your boss expects?

- Winning People Over

- What if there is no Third Alternative?

- Open Hostility

- Treat People with Kid Gloves or Hit them with a Hammer?

- Clock Watchers Redux

- At the Bottom of the Hill is… the Inventory Account

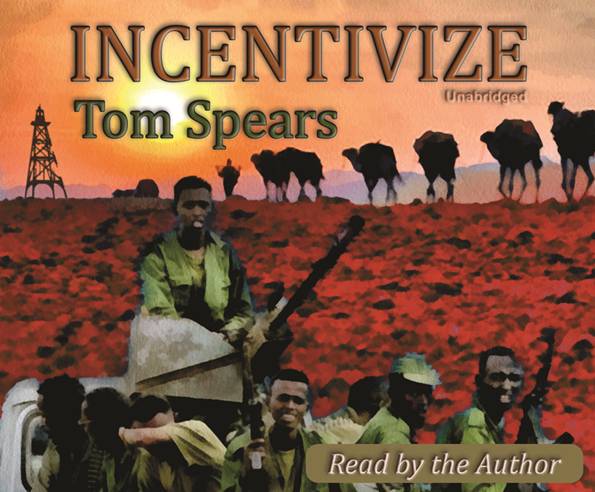

If you are intrigued by the ideas presented in my blog posts, check out some of my other writing. Novels: LEVERAGE, INCENTIVIZE, DELIVERABLES and HEIR APPARENT. Coming soon -- PURSUING OTHER OPPORTUNITIES

Non-Fiction: NAVIGATING CORPORATE POLITICS

To the right is the cover for INCENTIVIZE. This novel is about a U.S. based mining company, and criminal activity that the protagonist (a woman by the name of Julia McCoy) uncovers at the firm's Ethiopian subsidiary. Her discover sets in motion a series of events that include, kidnapping, murder, and terrorism in the Horn of Africa.

My novels are based on extensions of 27 years of personal experiences as a senior manager in public corporations.