There are times when it makes sense to point out the folly of others, and times when it is better to hold your tongue and let them suffer with their own decisions.

As a boss, I often found myself wishing that subordinates would challenge my assertions, pointing out (of course, in a kind and gentle way) where there might be holes in my reasoning. I knew I was limited by my own preconceived notions and prejudices and needed insightful critique. Having subordinates simply agree with me didn’t add value.

On the other hand as a subordinate, I rarely found myself inclined to provide such feedback. There were several reasons for this, some legitimate, some political, and some based solely on emotion.

When to legitimately keep your trap shut

There are several circumstances where you will want to avoid pointing out someone else’s errors. A prime instance would be when you have an opinion, but it falls outside of your expertise and/or area of responsibility. Another time might be when pointing out the obvious has virtually zero chance of successfully changing the person’s mind.

For example, at one employer we weighed a significant acquisition during one of the corporate staff meetings. The deal was essentially a “doubling down” in an industry where we’d already made one (mostly unsuccessful) acquisition. The theory, as I understood it, was that by owning both companies we could increase our critical mass allowing us to reduce costs and achieve a modicum of pricing power. The problem, as I saw it, was that the industry was prone to wild demand swings, and the patience level for extracting the “synergies” was exceptionally low given our already suspect track record.

I elected to not point out these problems, ones that seemed obvious to me.

There were a couple of reasons for this. First, the deal was not in my business unit, and as the “new guy” (I’d been employed by the company about a year), I didn’t think my opinion would carry much weight. Perhaps a bigger factor was that the corporate sponsor for the deal was my boss, the CEO. He’d already made up his mind on the transaction, and I could see that no amount of arguing by any of his direct reports – line or staff – was going to change the decision.

In that instance, the deal was completed but the new acquisition did nothing to solve the problems of the original one. A former owner of the acquired company set up a competing business, and made a mess of the most profitable business segment. Additionally, after about a year the entire industry entered a deep and prolonged downturn. Some of the things I was worried about turned out to cause problems, others didn’t. My prognostication was far from perfect, but I was more accurate than the guy calling the shots.

In short, the strategy turned out to be disastrous.

Politics are often a factor

There are times when it is politically infeasible to point out obvious flaws in plans and strategies. You always need to consider whether speaking out against someone’s fondly held idea, project, belief, opinion, or the quality of their execution, will create more problems than it is worth.

The problem with a political argument to keep silent is that it is a very small leap to using “politics” as a rationalization for not speaking up, even when something else is really behind the decision (fear, for instance). In many such situations, I’ve found both of these motives (a rational assessment of political consequences, and politics as an excuse) being a part of the equation. And I’ve been as guilty as anyone of blending the two.

Is your hesitation to speak out against a proposal for a new capital asset really because you want to ally yourself with the person making the proposal (like a peer or your boss), or are you just afraid of getting into a nasty, loud squabble?

In one real life example, I was running a business unit that was having major problems bringing in raw materials immediately following the installation of a new computer system (ERP). The new system brought over incorrect and obsolete lead time data from the old system, and our “expert” quit when it became clear he was going to be transferred to the corporate procurement group. We were running out of everything we needed to produce the products.

I called a meeting to discuss this, but my boss at the time immediately took control of my meeting. We already had inventory broken into three categories – “A” the high volume items, “B” the medium volume items, and “C” the low volume items. At least 80% of the parts we bought were in group “C” making the fixing of that group the most problematic. My boss suggested we purchase “a year’s worth” of every “C” item as a temporary fix, thus allowing the available manpower to focus on correcting lead times for the other two groups.

At the time I knew this would result in major problems. We only had history to base the “year’s worth” orders on, and the product line wasn’t static and neither was the market. I figured we’d end up with 5 years of some items, and run out of others after only a few months.

But I kept my mouth shut. The reason? My boss had been a tremendous ally, and I didn’t want to risk alienating him – particularly with a public challenge.

It would have been fine if I would have then taken up the issue with him in private, but that’s where the “fear factor” entered the equation. This boss was bombastic and very hard to convince he was wrong. And he had a bad temper. I knew I should have challenged him in private, but I chickened out.

We ended up with a massive influx of inventory, with predictable results.

Fear of…

Confrontation. Public humiliation. Ridicule. Censure. Embarrassment. These are the things that can drive a person to hold back. If you’re a boss and you want open, honest, helpful feedback, you must eliminate these behaviors from your managerial portfolio. If you’re a subordinate, then sometimes you just have to suck it up and demonstrate some courage.

The cover of my latest novel, EMPOWERED, released October 12, 2014. You can find it on Amazon here.

I can think of a few instances where I took on the fear and pointed out an obvious flaw in someone’s plans/thinking. Usually, the consequences were not as bad as I’d worried they might be, although there were usually consequences of some sort. All too often I took the easy way out – silence.

In one example where I overcame my fears and took on my boss, I found myself telling him his pet project (in this case a new manufacturing plant) was never going to hit the return rates that had been projected in the original project. At the time I knew full well that he’d had a hand in crafting the analysis.

While doing this didn’t have any immediate negative consequences, it was the beginning of the end. Afterward our relationship, which was never particularly friendly, became distant. In a few instances he publically attacked me.

But it was the right thing to do. Otherwise I (or in this case, my successors) would have spent an eternity explaining why the plant wasn’t achieving the project’s original financial projections.

Conclusion

Pointing out the folly of others is often politically risky, and is rarely a comfortable process. You might stir up a hornet’s nest, but you might also save the company from making a costly mistake. Sometimes it might even enhance your reputation.

When you find yourself tempted to hold your tongue, carefully examine your motives. If it is a pointless exercise, or you lack the credibility for your observations to be taken seriously, then by all means, remain silent. If your motives are political or emotional, you should carefully weigh the potential rewards and consequences of speaking out. At least some of the time, you should overcome your fears and point out the errors of bosses, peers, and subordinates. 2.1

Other Recent Posts:

- Looking Past the Façade

- What Was, What Is, What Could Have Been

- Stay in the Saddle, or Shoot the Horse?

- In the End, You Must Answer to Yourself

- Fast, Good, or Cheap – Pick Two

- They Don’t Call it “The Bleeding Edge” for Nothing

- Dying By the Sword

To find other blog posts, type a keyword into this search box, or check my Blog Index…

My LinkedIn profile is open for your connection. Click here and request to connect. www.linkedin.com/in/tspears/

If you are intrigued by the ideas presented in my blog posts, check out some of my other writing.

Novels: LEVERAGE, INCENTIVIZE, DELIVERABLES, HEIR APPARENT, PURSUING OTHER OPPORTUNITIES, and EMPOWERED.

Non-Fiction: NAVIGATING CORPORATE POLITICS

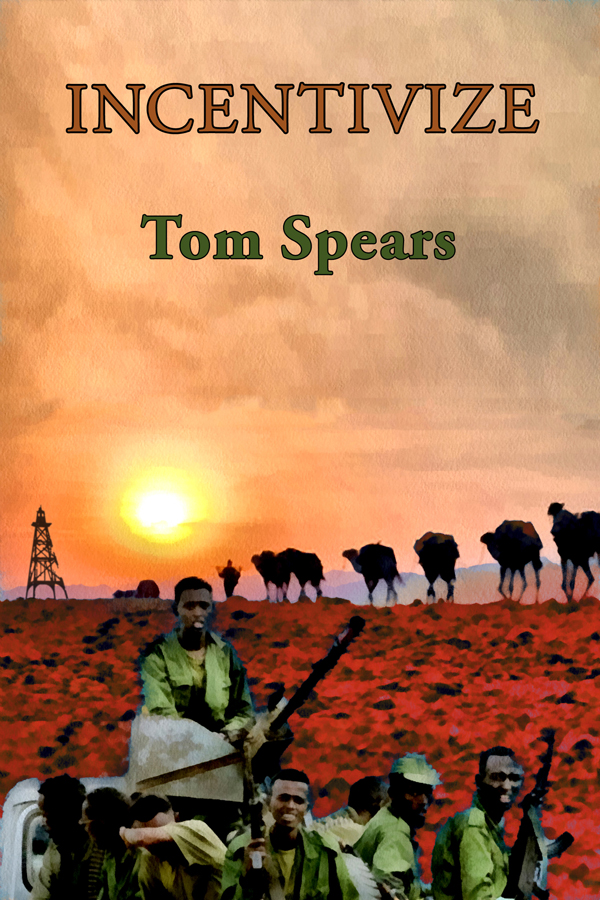

To the right is the audiobook cover for INCENTIVIZE. This novel is about a U.S. based mining company, and criminal activity that the protagonist (a woman by the name of Julia McCoy) uncovers at the firm's Ethiopian subsidiary. Her discover sets in motion a series of events that include, kidnapping, murder, and terrorism in the Horn of Africa.

My novels are based on extensions of 27 years of personal experience as a senior manager in public corporations.