Be careful with whom you unburden yourself.

It probably seems like this advice is so basic that it hardly needs to be said, but I can't count the number of times I've seen people suffer incredible political damage because they offered their opinions and observations to the wrong person.

The vast majority of people will know better than to shoot their mouth off about "something" to the owner of the "something," but many seem completely clueless when it comes to speaking with the owner's allies. If a contact has a link back to the owner, you better carefully evaluation that importance of that linkage compared to the value of your own mutual alliance.

To be safe, I recommend you adopt the following rule of thumb:

"Always assume whatever you disclose to another employee (or their extended contacts, such as a spouse or outside consulting resource) will immediately find it's way back to the person most likely to be angered or offended by the remark."

Of course, we can't operate this way at all times. The basis for most political alliance building in organizations is a concept I'll call "progressive self-disclosure," with an emphasis on the "progressive" element. Progressive self-disclosure starts with the confession of small, less dangerous opinions, and requires a quid pro quo from your partner to move forward to more serious stuff. Only through multiple conversations and multiple disclosures going each direction can you reach a level of mutual comfort that allows you to openly discuss the most sensitive issues.

In order to participate in the political processes going on around you, you'll certainly need allies, and generally the best allies will share a certain like-mindedness with you when it comes to how things in the organization are going. Without identifying potential allies, and testing their willingness to partner with you through progressive self-disclosure, you're not going to get very far.

Unfortunately, this process is easy to screw up. And sometimes expert politicians will lay in wait just hoping you'll disclose something damaging that they can use immediately or at a future time.

As recently as a few years ago, I made such a mistake. A potential ally fooled me into disclosing way too much without adequate quid pro quo. The mistake occurred after my boss took an action that peeved me, and I wanted to discuss the situation and it's implications with this pseudo-ally. It had previously seemed there was good rapport between the two of us, and I thought we were of the same mind when it came to our opinion of our mutual boss. But I miscalculated.

I overestimated the importance of our relationship. He listened to me offer my opinions about the situation, which included some pretty unflattering comments about my boss's management style, seemed to sympathize with my plight, and then offered his advice (he'd been at the company much longer than I). I left feeling satisfied.

What I didn't know was that he was in the boss's office a few minutes later, repeating the content of the conversation. That put me in a tough position next time I met with the boss, and resulted in a confrontation (which worked out okay in the long run, but was pretty uncomfortable). I instantly knew the information could have only come from one place.

My pseudo-ally proved that he was willing to sacrifice our brief and inadequately deep partnership in favor of scoring points with the boss.

I never trusted him again, but by that stage the damage was done.

In reflecting on how the situation had occurred, I realized the pseudo-ally was putting on an act that I should have seen through. The tell-tale sign -- he wasn't offering enough "at risk" opinions on his side, not enough quid pro quo. When I willingly provided a few too many tempting morsels, he was quick to sell me down the river.

When offering your personal opinions, building alliances, and engaging in progressive self-disclosure, make sure to pay attention to whom you are talking. It is important to know who they might be connected to, and where that connection might be more valuable than their connection to you. And be careful about the kind of ammunition you might be putting in their hands, and what they're giving back to you. Practice "mutually assured destruction" when it comes to disclosure in order to reduce the risk of betrayal. And don't be in a rush. Political alliances are built over time, and tested with relatively benign information before progressing to the point of disclosing dangerous opinions. Handling them any other way is just asking for trouble. 17.2

Other Recent Posts:

- Using Structure to Solve Your (Personnel) Problems

- Letting Sleeping Dogs Lie

- Entitled

- Picking Your Own Team

- Nobody Gives up Top Talent

- Confiding in a Political Dunce

- Cornering a Rat

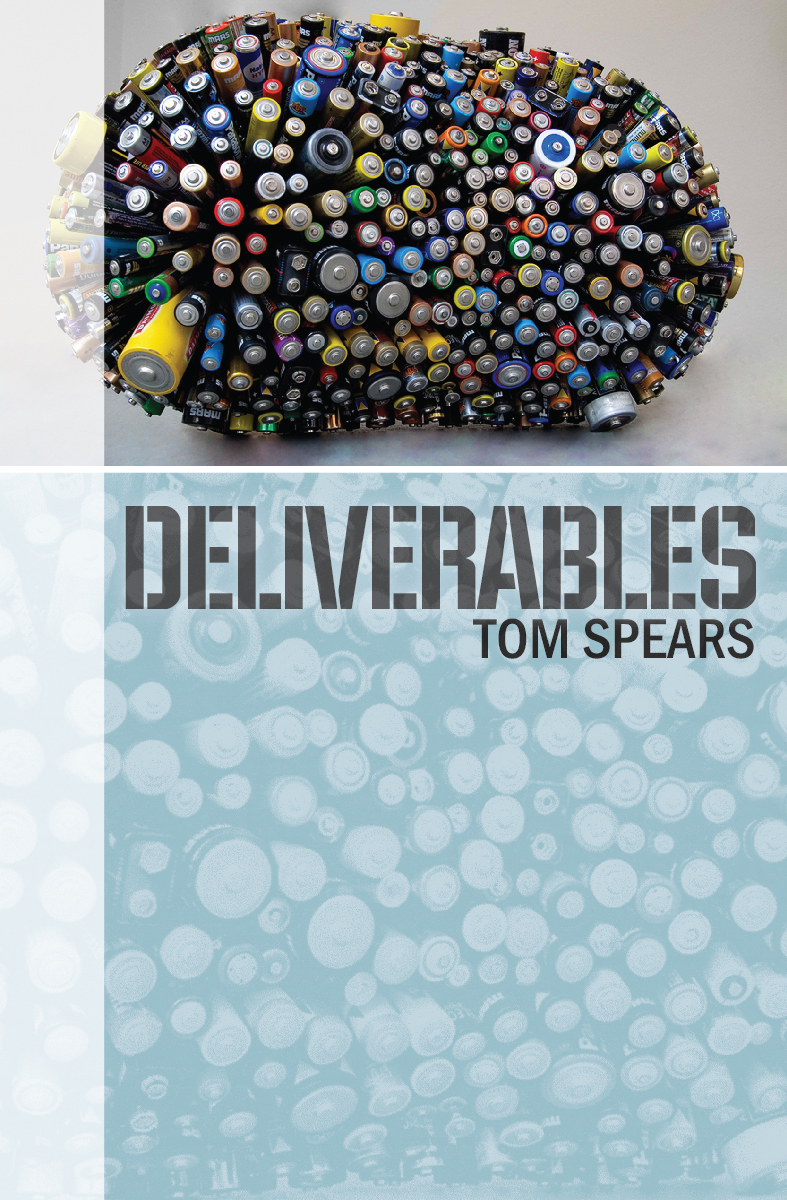

If you are intrigued by the ideas presented in my blog posts, check out some of my other writing. Novels: LEVERAGE, INCENTIVIZE, DELIVERABLES and now HEIR APPARENT (published 3/2/2013) -- note, the Kindle version of DELIVERABLES (a prequel to HEIR APPARENT) is on sale for a limited time for $2.99.

Shown here is the cover of NAVIGATING CORPORATE POLITICS my non-fiction primer on the nature of politics in large corporations, and the management of your career in such an environment.

My novels are based on extensions of my 27 years of personal experience as a senior manager in public corporations. Most were inspired by real events.